Is this a situation you recognise? For some years you have been negotiating with the branch or a supplier of a large international company which by now has also firmly established itself in the ‘low wage countries’. You negotiate about collective bargaining agreements and you can’t manage to reach a good consensus about wages and working conditions for employees. Even though you know that the company

has arranged these things properly in its country of origin. So what do you do?

As a trade union leader you have a particular responsibility within your company, sector or industry: you protect and promote labour rights. It’s certainly not easy to protest against abuses or wrongs at the local branches of foreign companies.

With the help of your international network of trade union organisations and your status as a partner organisation of CNV Internationaal, you can in fact play an important role here. That’s because the CNV trade unions work to benefit people and the environment, and look further than the national boundaries. After all, CNV leaders, officials or members of the Works Council are active within international companies in the Netherlands that also operate branches abroad or purchase from foreign suppliers. Sustainability and international solidarity are two of CNV’s core values. We believe it is important that employees’ human rights are respected all over the world.

For the original source, please click here.

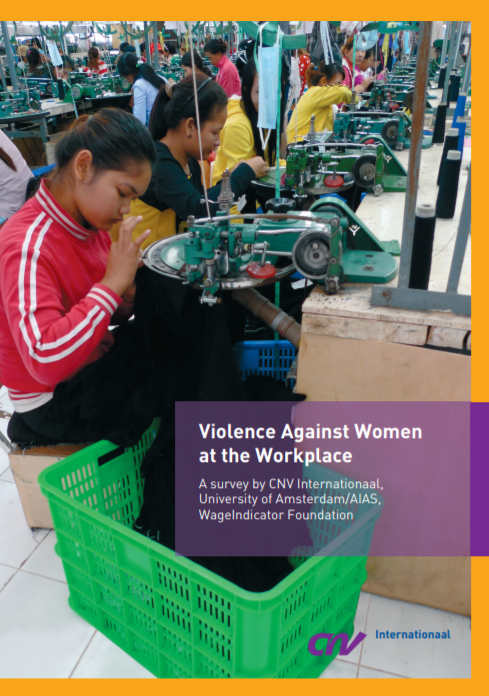

Violence against women at the workplace is a major problem, though the statistical evidence is not well developed for many countries. This report aims at gaining a better insight into the extent to which working women are facing violence at work. The research focussed on the extent and characteristics of violence against women at the workplace and on the perpetrators of violence, notably bosses, co-workers or clients/patients/customers/pupils and similar. It focusses on women in the working age population (15-65 years of age), hence adolescent and adult women.

Our research focussed on sexual harassment and bullying at the workplace. It did neither cover domestic violence against women nor human trafficking and forced prostitution, because the causes and consequences of these phenomena are different from those of violence at the workplace, and so are the statistics. The research also does not include indirect violence against women, such as job insecurity due to flexibility of employment contracts. In addition, it will also not focus on gender-biased issues related to health and safety at work.

The research focussed on violence against women at the workplace in four countries: Honduras, Indonesia, Moldova, and Benin. Each country report starts with an overview concerning the female workforce in that country, followed by a description of the legal framework concerning violence at work. It then tries to provide an overview of the institutional responses to violence at work. Although data on the incidence of violence against women at work are mostly quite scarce, the research tries to estimate the frequencies of these types of violence in the countries at stake. Then, the reports provide anecdotal evidence of violence at work, and end with conclusions and recommendations.

For the original source, please click here.

The case studies in this research describe how two RSPO-certified palm oil companies structurally violate the labour rights of their workers. In both cases, workers are forced to work unpaid overtime in order to reach unrealistic production targets. Furthermore, these targets have motivated workers to bring their wives and children to work, thus giving rise to child labour. Other rights violations found in the field research included union busting, workers never receiving employment contracts, inadequate PPE provision and inadequate medical services. Thus, many workers’ rights violations were found that breach the RSPO standard, international law, Indonesian law, or all of the above.

This report provides a brief discussion of the implementation of the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights in Indonesia, in an attempt to showcase some of the pitfalls that hamper this process. Two of these are uncertainty over whether Indonesia has a monist or a dualist legal system, and organisational and political issues with developing the country’s National Action Plan. The lack of implementation and enforcement of the UNGPs in Indonesia are illustrated by the company case studies, and the company’s violations of rights enshrined in UN conventions, such as children’s right not to work.

Furthermore, the international standing and reputation of the Roundtable for Sustainable Palm Oil (RSPO) is discussed. Dutch companies that use palm oil in their products have joined the RSPO in an attempt to make their palm oil supply chains more sustainable and to ensure that the palm oil they buy has taken place free of labour rights violations and environmental degradation, among other criteria. NGO reports show that, at least on an incidental basis, the RSPO certifies palm oil produced by companies that commit exactly the types of human rights and environmental violations that motivated the creation of the RSPO.

Although further research would be needed to underwrite such a sweeping statement about the RSPO, the case studies presented in this report show that RSPO certification is not necessarily an assurance of sustainable palm production, and thus give cause for scepticism towards the initiative. Companies should therefore not depend solely on certification, but should undertake their own supply chain due diligence to ensure their business partners do not commit labour and human rights violations, so that they can safeguard their own compliance with the UNGPs.

For the original source, please click here.

This is a study of Social Dialogue in developing countries. It was commissioned by the Norwegian Agency for Development Cooperation (Norad) on behalf of the Royal Norwegian Ministry of Foreign Affairs (MFA) in November 2010. It was prepared by Michael Fergus, partner in Nordic Consulting Group AS. The purpose of the study is to map experience with dialogues on socio‐economic issues between government and organisations in productive sectors, and possibly civil society organisations, in selected developing countries. In countries where a system of social dialogue has been established the study also assesses whether the experience is of interest for other countries to learn from. Norway may then consider supporting some form of interaction between countries in the South. It is not the purpose of the study to try to assess whether the Norwegian model of social dialogue can be copied into different political systems and cultures.

For the original source, please, click here.

This paper looks at past economic crises to identify lessons that can be learned from industrial relations developments in different regions and varying circumstances. The paper describes the development of social dialogue in the early period of the current crisis in order to inform the reader about the forms and content of crisis-related social dialogue in different parts of the world and to provide national examples. It concludes by suggesting policy options. The paper also contains tables of national and enterprise-level cases documenting the role of social dialogue and industrial relations in addressing the employment impact of the crisis.

For the original source, please click here.

Trade Union Co-Financing Programme 2017-2020 Summary

CNV Internationaal Foundation is a civil society organisation, connected to the National Confederation of Christian Trade Unions (CNV) in the Netherlands. CNV Internationaal has worked with trade unions in developing countries since its establishment in 1967. Together with its partner organisations, CNV Internationaal protects and promotes workers’ rights by means of a consultative and coherent model, based on Christian social traditions. Social dialogue, trade union pluralism and workers’ individual responsibility are key values. CNV Internationaal’s mission is to contribute to Decent Work in developing countries by strengthening the position of workers in the formal and informal economy. CNV Internationaal focuses on social dialogue, labour rights in supply chains and youth employability.

This study covers the development of social dialogue in Indonesia from the end of the Suharto regime, in 1998, until 2015 and more specifically during the period that goes from 2004 to 2015. It is aimed at analysing specific examples of social dialogue taking place in the period in question, and assessing how the results of this dialogue amongst social partners has contributed to socio-econonomic development in Indonesia. The purpose of the analysis is also to highlight the importance of the “conditions” in which social dialogue can flourish and can be effective for development. These conditions are based on the freedom of association, collective bargaining, the willingness of social partners to engage in dialogue, and the supporting role of the State. The latter are “enabling conditions” for social dialogue to be relevant for socio-economic development in every country. The current study focuses its analysis on specific positive past experiences. However, it has to be noted that unfortunately the situation in Indonesia has recently changed dramatically. The country is experiencing a severe drawback in terms of respect of fundamental labour rights, resulting in a disruption of social dialogue. The International Labour Organisation’s (ILO) Convention No. 87 on Freedom of Association and Protection of the Right to Organise was ratified by Indonesia straight after the fall of the Suharto regime, and important progress was made in the country in the years following the transition period. However, these rights are currently under threat as illustrated by the arbitrary arrests and detention of trade unionists, imprisonment and fines issued to workers taking part in peaceful strikes and an inadequate legislation on freedom of association for civil servants.1 Other setbacks to social dialogue, over the last year, are those related to the minimum wage setting process. Until October 2015, minimum wages were negotiated through social dialogue. This changed following the introduction of a new law to calculate minimum wages through a formula based on inflation and GDP growth. The new law has undermined negotiations, rendering them superfluous, and threatens the remarkable progress achieved in the past years. It has also lead to a number of protest actions by the Indonesian unions in a struggle to reinstall dialogue.2 This of course is undermining the positive achievements previously reached, putting at serious risk the whole developmental and democratic process in the country. This study has therefore to be taken in its specific context as a snapshot of what social dialogue can achieve with the good will of its actors.

1. See the Provisional Record of the Report of the Committee on the Application of Standards of the 105th Session of the International Labour Conference (2016) pp.50-55

2. The International Trade Union Confederation has recurrently manifested its support to the struggle of the Indonesian workers and has continuously denounced violations of their rights, reported in its Survey of Violations of Trade Union Rights. As a result of the deterioration of rights, Indonesia has been downgraded, in the International Trade Union Confederation’s Survey of Violations of Trade Union Rights, from a rating of 4, which implies a situation of systematic violations of rights to a rating of 5, implying no guarantee of rights

To see the original document, click here.

This report is part of a series produced by the Non-Judicial Human Rights Redress Mechanisms project, which draws on the findings of five years of research. The findings are based on over 587 interviews, with 1,100 individuals, across the countries and case studies covered by the research. Non-judicial redress mechanisms are mandated to receive complaints and mediate grievances, but are not empowered to produce legally binding adjudications. Te focus of the project is on analysing the effectiveness of these mechanisms in responding to alleged human rights violations associated with transnational business activity. The series presents lessons and recommendations regarding ways that:

The Non-Judicial Human Rights Redress Mechanisms Project is an academic research collaboration between the University of Melbourne, Monash University, the University of Newcastle, RMIT University, Deakin University and the University of Essex. The project was funded by the Australian Research Council with support provided by a number of nongovernment organisations, including CORE Coalition UK, HomeWorkers Worldwide, Oxfam Australia and ActionAid Australia. Principal researchers on the team include Dr Samantha Balaton-Chrimes, Dr Tim Connor, Dr Annie Delaney, Prof Fiona Haines, Dr Kate Macdonald, Dr Shelley Marshall, May Miller-Dawkins and Sarah Rennie. The project was coordinated by Dr Kate Macdonald and Dr Shelley Marshall. Te reports represent independent scholarly contributions to the relevant debates. The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the organisations that provided support. This report is authored by Tim Connor, Annie Delaney and Sarah Rennie. Correspondence concerning this report should be directed to Tim Connor, tim.connor@newcastle.edu.au. To see the original document, click here.

This paper is one of a series of national studies on collective bargaining, social dialogue and non-standard work, conducted as a pilot under the Global Product on ‘Supporting collective bargaining and sound industrial and employment relations’ in collaboration with the ILO Decent Work Team for South Asia. The national studies aim at identifying current and emerging non-standard forms of work arrangements within which workers are in need of protection; examining good practices in which those in non-standard forms of work are organized; and analysing the role that collective bargaining and other forms of social dialogue play in improving the terms and conditions as well as the status of non-standard workers, and identifying good practices in this regard. The paper provides an overview of the situations facing informal, contract and outsourced workers, and how labour law regulates their terms and conditions of work. It analyses both legal and practical constraints in organizing such workers and the challenges to promoting effective social dialogue and collective bargaining. It also examines how the financial crisis has affected these workers negatively. Interestingly, the number of collective agreements increased in Indonesia during the early years of the crisis, but the trade unions’ priority was to secure the jobs of permanent workers. Some innovative practices to improve the situation and status of informal, contract and outsourced workers are identified in the paper. Some trade union confederations have been active in organizing informal workers, including those outside employment relationships, casual workers, domestic workers and migrant workers, based on the sectors they belong to. These confederations adopted a strategy that offer such workers direct membership, settle disputes on their behalf, raise their bargaining position, and provide training opportunities and more protection in terms of both income and job security. In Batam’s export processing zones (EPZs), trade unions in the metal, machine and electronics sectors have also been successful in organizing contract and outsourced workers, which resulted in a number of such workers being shifted to permanent status. The key to success in these cases was building solidarity between permanent workers and contract and outsourced workers. The paper concludes with a number of policy recommendations addressing issues regarding informal, contract and outsourced workers. It identifies a need for various kinds of action, such as improved compliance with labour law and regulations, strengthened labour inspection services, increased capacity of both workers’ and employers’ organizations, and strengthened solidarity among trade unions. DIALOGUE working papers are intended to encourage an exchange of ideas and are not final documents. The views expressed are the responsibility of the author and do not necessarily represent those of the ILO. We are grateful to Ratih Pratiwi Anwar and Agustinus Supriyanto for undertaking the study, and commend it to all interested readers. To see the original document, click here.